When the U.S. Constitution comes up in conversation, we rarely stop to think about what lies behind this dry legal term. In reality, it is not just words on paper. It is a symbol of an entire era, the foundation of the nation, and a kind of “road map” for democracy that has guided not only America but the world for over two hundred years.

Picture the late 18th century. Europe is in turmoil: revolutions, wars, monarchs struggling for power. At the same time, a group of people in the distant American colonies decides to create a document that does more than regulate power — it changes its very nature. Instead of rule by a king — rule by the people. Instead of hereditary power — elected leadership. Instead of dictatorship — balance and checks.

While European constitutions were rewritten dozens of times, the American Constitution has endured for over 200 years and remains relevant. Yes, amendments have been added, but the very foundation laid in Philadelphia in 1787 proved so strong that it still functions today. The Constitution became a living document capable of adapting to new realities without losing its essence.

Why does this matter? Because behind the simple words about “justice” and “freedom” lies an entire philosophy — the idea that the government exists for the people, not the other way around. This philosophy allowed the United States to survive a civil war, crises, world conflicts, and still maintain stability.

Interesting fact: In the 1930s, when Harvard students conducted a survey on knowledge of the Constitution, it turned out that many knew more about baseball rules than the Bill of Rights. Today, the situation has changed little: according to surveys, one in three Americans cannot name a single amendment.

It may seem that such a brief text cannot encompass everything. But the strength of the U.S. Constitution lies precisely in its conciseness. It sets fundamental principles, while details are filled in by amendments and Supreme Court decisions.

And here is the main question: how did an 18th-century document come to shape life in the 21st century? Let’s find out.

The U.S. Constitution is the shortest functioning constitution in the world. It contains only about 4,600 words (excluding amendments). By comparison, the Constitution of India exceeds 145,000 words.

The Birth of the Constitution: From Colonies to a United Nation

The story of the U.S. Constitution is not just a tale of lawyers working behind closed doors, but a dramatic account of struggle, compromise, and bold ideas. It all began after the War of Independence (1775–1783), when 13 former British colonies decided they no longer wished to answer to London. They won the war, gained their freedom, but quickly realized that victory was only the beginning.

The first attempt to unite the new states was a document called the Articles of Confederation. It envisioned a union of the colonies, but the federal government’s powers were extremely limited. The Congress could not levy taxes, there was no unified army, and trade rules varied from state to state. Essentially, each former colony lived its own life. The central authority could only request, not enforce.

As a result, the country resembled a “patchwork quilt,” with each part pulling in its own direction. Without reforms, the young republic’s future was uncertain. That’s when the idea arose to convene a Constitutional Convention to draft a single document that would turn the union of states into a true nation.

- 01. The Philadelphia Convention of 1787

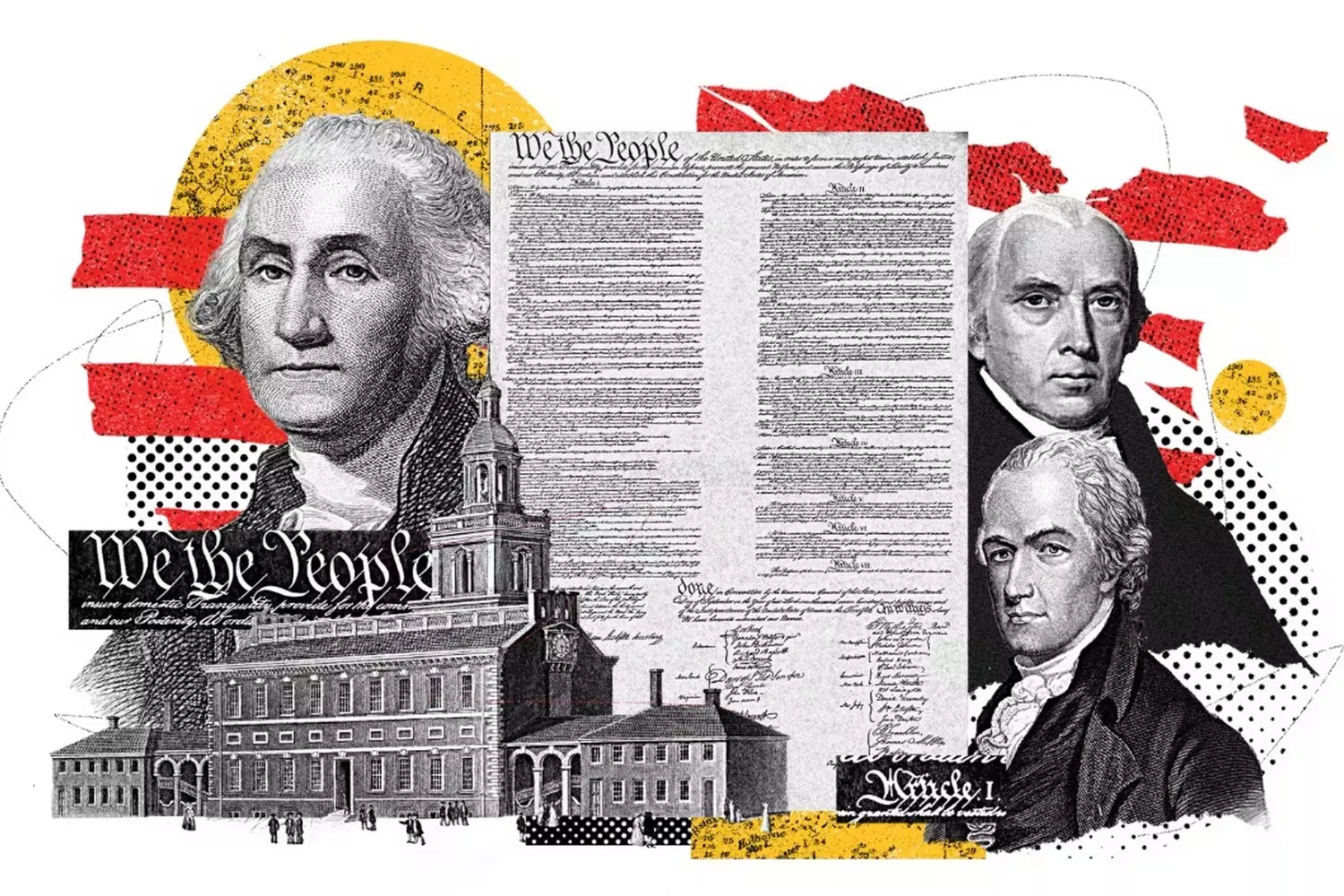

In the spring of 1787, 55 delegates from 12 states (Rhode Island refused to participate) gathered in Philadelphia. This event became known in history as the Constitutional Convention. It brought together a kind of “dream team” of political thought at the time:

- George Washington

Hero of the War of Independence, future first president. - James Madison

A brilliant thinker, later called the “Father of the Constitution.” - Alexander Hamilton

An energetic and ambitious politician, advocate for a strong federal government. - Benjamin Franklin

A wise diplomat and one of the most respected figures in the colonies.

These men represented different interests and had varying visions for the country’s future.

- 02. Battles of Ideas and Compromises

Debates focused on key issues:

- The President

Some wanted a strong executive branch; others feared creating a new “king.” - The States

Smaller states feared domination by larger ones. The question arose: how should states be represented in Congress — equally or based on population? - Slavery

Southern states insisted on its continuation, while northern states viewed it as incompatible with freedom principles.

Here, major compromises were born. For example, the so-called “Great Compromise” created a bicameral Congress: the Senate (equal representation for all states) and the House of Representatives (representation based on population).

The “Three-Fifths Compromise” allowed southern states to count enslaved people as 3/5 of a person for population calculations. It seemed odd and harsh, but it was a concession to preserve the union.

- 03. Signing the Constitution

Four months of debates, heated arguments, and negotiations resulted in the creation of a text that changed history. On September 17, 1787, the U.S. Constitution was signed.

Not all delegates were satisfied. Some thought the document gave too much power to the central government, others felt it did not protect citizens’ rights enough. But everyone understood: an imperfect Constitution was better than no unity at all.

Thus, a document was born that transformed a collection of disparate states into a nation. Its principles — separation of powers, checks and balances, and the rule of law — remain at the core of the U.S. political system today.

The Preamble of the U.S. Constitution: Words That Changed History

When we hear the word “preamble”, we usually imagine something dry and formal, like the introduction to a legal document. But in the case of the U.S. Constitution, it’s different. Its preamble is not just an introduction — it is a manifesto, expressing the philosophy of an entire nation in just a few lines.

The text begins with simple yet powerful words:

“We the People of the United States…”

These three words contain a revolution. In the 18th century, most countries were ruled by monarchs, and laws came from the top — from kings, emperors, or sovereigns. In America, it was different. The Constitution declared that the source of power is the people. Neither a king, nor a parliament, nor even the elite — only the citizens of the country.

- 01. What each part of the preamble means

The preamble is short, but it acts like a “road map” of values:

- “Form a more perfect union”

The states wanted not just a union on paper, but true unity. - “Establish justice”

For the first time, the idea of equal rights under the law was proclaimed. - “Ensure domestic tranquility”

The country had just emerged from war, and internal peace was vital. - “Provide for the common defense”

Protection against external enemies became a key task. - “Promote the general welfare”

Not the wealth of the elite, but the well-being of the people. - “Secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity”

Focus on the future: the Constitution was created not for one generation, but for all that follow.

- 02. Why the preamble became a symbol

It might seem like just beautiful words. But for Americans, they became a kind of promiseInterestingly, the preamble itself has no legal force — it does not create legal rules. Yet judges, presidents, and activists quote it to remind people of the essence of the Constitution. It acts as a moral compass, pointing the way even if it does not lay out the route itself. - 03. The preamble as part of American culture

Today, every American knows these lines. They are taught in schools, quoted in movies and at rallies. They appear solemnly in history textbooks but remain part of everyday life.

It is no coincidence that many scholars call the preamble “the most famous phrase of American democracy.” It became a symbol that in America, power belongs not to the ruler, but to the people — something that made the Constitution unique for its time.

Seven Pillars of American Statehood

If the preamble sets the spirit of the Constitution, then its seven articles form the framework on which the entire structure of the American republic rests. They are short in text but deep in meaning: the Founding Fathers established a delicate balance between freedom and order, between the federal center and the states, between laws and courts. Below is a detailed, clear breakdown of each article: what it contains, why it matters, and how these provisions have influenced history and remain relevant today.

Article I — Legislative Power: the Bicameral Congress and its “to-do list”

- 01. What it provides

The first and longest article creates Congress — a bicameral legislative body consisting of the House of Representatives and the Senate. It lists Congress’s main powers: making laws, levying taxes, issuing money, regulating interstate commerce (commerce clause), declaring war, establishing lower courts, and more. It also sets procedural rules: election procedures, qualifications for representatives and senators, session rules, immunities, and sanctions. - 02. Key elements and meaning

- Bicameralism

A compromise between large and small states: the House reflects population, the Senate ensures equality among states. - Enumerated powers

Congress has only the powers listed; but the “necessary and proper” clause provides flexibility to fulfill its duties. - Commerce clause

This provision for regulating trade became a powerful tool to expand federal authority as the economy developed.

- 03. Practical application

This text grew into a powerful legislative machine capable of responding to crises: financing the army, collecting taxes for war, creating national programs. Thanks to the “necessary and proper” clause, the federal government could establish institutions and regulate areas unknown in the 18th century (banking, social programs, industry regulation). - 04. Historical and modern “points of influence”

- Conflict between Congress and the president — an enduring theme in American politics (e.g., budget disputes, declarations of war).

- The 17th Amendment (1913) changed the method of electing senators: from state legislatures to direct election by citizens.

Article I is about representation, money, and the power to make rules. It sets the “rules of the game” for all public governance.

Article II — Executive Power: the office and powers of the President

- 01. What it provides

Article II establishes the offices of President and Vice President, outlines the election procedure (via the electoral college), and lists powers: executive authority, commander-in-chief of the armed forces, treaty-making (with Senate consent), appointment of judges and officials (with Senate advice and consent), law enforcement, and pardon powers. - 02. Key elements and meaning

- Commander-in-Chief

While exercising executive power, the President operates within laws passed by Congress. - Electoral system

Designed to balance direct voting with the role of states. - Control mechanisms

Impeachment and removal (House impeachment, Senate trial), plus oversight via appointments and budget.

- 03. Evolution and practice

While the text provides a basic set of powers, presidential authority has expanded over time: executive orders, increased role in foreign policy and national security in the 20th century. The Constitution does not mention all modern functions (e.g., party leadership), but practice and tradition filled the gap. - 04. Amendments affecting Article II

- 12th Amendment (1804)

Changed the electoral process (separating votes for President and Vice President). - 22nd Amendment (1951)

Limited terms (no more than two elections).

Article II establishes a strong but limited executive — balancing effective governance with safeguards against tyranny.

Article III — Judicial Power: courts and, most importantly, the Supreme Court

- 01. What it provides

Article III creates the federal judiciary and establishes the Supreme Court, while allowing Congress to create lower courts. Powers include hearing cases involving the Constitution, federal law, and interstate disputes. Judges are appointed by the President with Senate approval and serve “during good behavior” — effectively for life. - 02. Key elements and meaning

- Judicial independence

Ensured through lifetime appointments and salary protection. - Jurisdiction limits

Not all disputes are federal; many matters are handled at the state level.

- 03. Most important practical effect

The Constitution did not explicitly grant courts the power to strike down unconstitutional laws, but in 1803 the Supreme Court, in Marbury v. Madison, established judicial review — the ability to evaluate the constitutionality of laws and government actions. This made the judiciary a key arbiter of power and meaning in the Constitution.

The Constitution does not fix the number of Supreme Court justices — that is determined by Congress. The number has changed over time; since 1869, there have been nine. Article III gave the nation judicial authority as guardian of the Constitution; judicial review ensured the courts a decisive role in interpreting the fundamental law.

Article IV — Relations between States: federalism in action

- 01. What it provides

Article IV regulates interactions between states and the federal government. Key provisions include:

- Full Faith and Credit — states recognize each other’s public acts and judicial decisions.

- Privileges and Immunities — citizens of one state cannot be systematically denied basic rights in another state.

- Extradition — returning fugitives between states.

- Provisions for admitting new states and federal property management.

- 02. Practical role

This article turns a collection of independent jurisdictions into a unified economic and legal zone: marriages, legal processes, and documents work across state lines. Without it, the federation would fragment into multiple “mini-states.”

Article IV is the practical “glue” of the federation: it ensures that rights and decisions are not confined to one state alone.

Article V — How to Amend the Constitution: amendment procedures

- 01. What it provides

Article V describes two ways to propose amendments and two ways to ratify them, providing both flexibility and high legitimacy:

- An amendment can be proposed either by two-thirds of both congressional houses or by a convention called by Congress at the request of two-thirds of state legislatures (the latter has never been used).

- Ratification requires approval by three-fourths of the states — either through their legislatures or special conventions (the convention method was used once for the 21st Amendment).

- 02. Why it’s deliberately complex

The de facto purpose of Article V is to ensure the Constitution’s stability, preventing sudden political upheavals from altering the foundation. Amendments are possible but require broad consensus. - 03. Examples in practice

- The Bill of Rights (the first 10 amendments) was proposed by Congress and ratified by the states shortly after the Constitution’s adoption.

- The 21st Amendment (repealing Prohibition) is the only case of using the convention procedure for ratification.

Article V combines stability with flexibility: the Constitution is not a statue — it can be changed, but changes require serious public agreement.

Article VI — Supremacy: when federal law is “above all”

- 01. What it provides

Article VI contains the Supremacy Clause: the Constitution, federal laws, and treaties “made under its authority” are the supreme law of the land. It also requires public officials to take an oath of allegiance to the Constitution and explicitly prohibits religious tests for office. - 02. Why it matters

Without a clear priority for federal law, the federation would be mired in endless disputes between states and the center. Article VI provides an unequivocal answer: in conflicts, state law yields to federal law. - 03. Additional points

- The article ensures that federal debts incurred before the Constitution (a legacy of the Confederation) are recognized and paid — vital for trust in the new government.

- The prohibition of religious tests underscores the secular nature of governance: access to office should not depend on faith.

Article VI is the legal “scalpel” resolving jurisdictional conflicts: federal law prevails.

Article VII — Ratification: how the document became law

- 01. What it provides

Article VII establishes the procedure for the Constitution to take effect: approval from nine of the thirteen states was required (through state ratifying conventions). This threshold was pragmatic: requiring all states would have been unrealistic. - 02. How it happened

In 1787–1788, states convened conventions, where fierce debates took place between Federalists and Anti-Federalists. Ratification progressed state by state, and by 1788 the Constitution began operating in the ratifying territories; by 1790, all states had joined.

Article VII is the practical “entry door”: it allowed the new legal order to become reality quickly, without requiring unanimity.

Conclusion: how the articles work together — key observations

- Balance, not tyranny of one power

The separation of powers in the first three articles creates a system of checks and balances: neither Congress, the president, nor the courts can operate unchecked for long. - Flexibility through amendments

Article V allows the Constitution to change — sometimes slowly, sometimes dramatically (e.g., Reconstruction after the Civil War and adoption of major amendments). - Federation instead of centralism

Articles IV and VI uphold federalism: states are autonomous but within the framework of shared law. - Practice outweighs text

Many key institutions (judicial review, executive orders, direct election of senators) developed not just through the text, but also via practice, precedents, and amendments.

When the delegates signed the Constitution, the atmosphere was a mix of celebration and anxiety: they understood they were creating not just a document, but a system that would outlive them. According to one account, Benjamin Franklin, upon leaving, looked at the sun emblem on the chair and almost asked, “Does the sun rise on the new Constitution, or is it setting?” — and in that question lay both uncertainty and great expectation.

Amendments and the Bill of Rights: How the Constitution Spoke the Language of the People

The Constitution was written to set the framework of power. But it quickly became clear that frameworks alone were not enough — guarantees for individual rights were necessary. In response to citizens’ concerns, the Bill of Rights emerged — the first ten amendments, a direct language of freedom and protection. Below is a detailed, lively, and clear account of their origins, meaning, evolution, and real-life applications.

- 01. From promise to text: the birth of the Bill of Rights

After the Constitution was signed, many asked: “Where are the people’s rights?” Anti-Federalists — advocates for greater local autonomy and cautious about a strong central government — demanded explicit guarantees. To secure ratification support, Federalist leaders promised amendments protecting freedoms.

In 1789, James Madison submitted a proposal to Congress: initially over twenty amendments, later reduced to twelve, and in 1791, ten were ratified as the Bill of Rights. These ten instantly became a “safety net” for individuals against potential government overreach. - 02. Why amendments, not part of the Constitution

The approach was pragmatic: the Founders knew that embedding extensive guarantees directly in the Constitution would be difficult. A separate amendment block acted as a clear promise and was easier to ratify. Additionally, amendments set a standard: if government actions conflicted with these principles, courts and society could refer to explicit law rather than vague interpretation. - 03. The first ten: concise yet powerful

Here’s a clear explanation of each amendment and examples of how it works.

- First Amendment — Freedom of speech, religion, press, and assembly

It makes nearly impossible any law banning criticism of the government or restricting religious practice; limits exist only where real danger arises (e.g., incitement to violence). This amendment is central to public discourse. - Second Amendment — Right to bear arms

Originally tied to the concept of a militia, its interpretation has evolved. In 2008, the Supreme Court recognized an individual right to own firearms for home self-defense, transforming gun regulation practice. - Third Amendment — No quartering of soldiers in private homes without consent

Seemingly quaint today, but in the 18th century, British practices made this a crucial freedom issue. - Fourth Amendment — Protection against unreasonable searches and seizures

Requires a court-issued warrant and is foundational for privacy and limits on government intrusion. - Fifth Amendment — Right against self-incrimination, double jeopardy, and guarantees of due process

Famous in popular culture as “I plead the Fifth”. It intersects criminal procedure, defendants’ rights, and investigative practice. - Sixth Amendment — Rights of the accused in criminal trials: speedy trial, jury, attorney

Ensures minimum standards of fair trial. - Seventh Amendment — Right to jury trial in civil cases (in certain situations)

- Eighth Amendment — Prohibition of excessive bail, fines, and cruel punishments

Frequently cited in debates over the death penalty and prison conditions. - Ninth Amendment — Enumeration of rights does not deny others

It reminds that not everything unlisted is lost. - Tenth Amendment — Powers not delegated to the federal government remain with states or the people

It enshrines federalism in action. The brevity of these amendments contributes to their power: much meaning packed into concise text.

- 04. Historical impact — major milestones

- Thirteenth Amendment (1865) — Abolition of slavery

A radical social shift: formally banned slavery, initiating a long struggle for real rights. - Fourteenth Amendment (1868) — Introduced “equal protection of the laws” and “due process” principles

Laid the legal foundation for civil rights and extended federal protections to states through incorporation. - Voting expansions — 15th (race), 19th (women), 26th (age 18) amendments reflect societal challenges. Altogether, 27 amendments exist, showing the difficulty of modifying the foundational text and the need for strong public consensus.

- 05. Judicial practice: text meets life

Amendments are not mere words; their meaning evolves in courts. Examples:

- Miranda v. Arizona (1966)

Origin of the famous “Miranda warnings” (right to silence, right to attorney), showing how the Fifth (and Fourteenth) Amendments shape police practice. - District of Columbia v. Heller (2008)

Key Second Amendment case: affirmed individual right to own firearms for home defense, sparking ongoing legal and political debates. These cases demonstrate that power comes not from text alone, but from the combination of text and judicial interpretation.

- 06. Why amendments are rare — and what it means

The process (Article V) requires two-thirds of both congressional houses or a convention called by two-thirds of state legislatures, then ratification by three-fourths of states. This makes amendments infrequent, but gives them weight and stability. The system balances flexibility and conservatism: the Constitution remains “living,” but changes occur slowly and with broad support. - 07. Interesting historical fact about originals

Some original Bill of Rights pages sent to states in 1789 were lost or missing for long periods; in the 20th–21st centuries, some “traveling” copies were recovered through complex efforts. These stories highlight the value of these documents, not just legally, but as historical artifacts. - 08. Modern challenges and debates

Amendments and their interpretation still spark heated discussions:

- Freedom vs. security

Where is the line between free speech and prohibiting incitement? How to maintain order without undermining liberty? - Right to bear arms vs. public safety

Courts interpret differently, and state laws remain battlegrounds. - Privacy in the digital age

The Fourth Amendment predates smartphones and the internet; applying it to new technology raises complex legal questions. These debates show that amendments are active tools, not museum pieces.

The Living Constitution: How an 18th-Century Document Remains Relevant in the 21st Century

When people think of the U.S. Constitution, they often imagine an old parchment in the National Archives, covered with formal, lofty words. But Americans call it a “living Constitution”, and it’s not just a figure of speech. The document evolves with society, responds to new challenges, and has remained the guiding framework of the nation for over two centuries.

- 01. The Supreme Court as a “living interpreter”

One of the main tools keeping the Constitution “alive” is the U.S. Supreme Court. Justices do more than read the text — they interpret it in the context of the modern world. Examples:

- Freedom of speech in the digital age

The First Amendment protects speech, but what about the internet, social media, and cyberbullying? The Court develops rules that consider technological change. - Right to bear arms

The Second Amendment was written for 18th-century militias, but today it involves debates over individual self-defense and gun regulation. The Court refines the balance between citizen rights and public safety. - Fourth Amendment and privacy

Protection against unreasonable searches now applies to smartphones, cloud storage, and digital data — issues the 18th-century authors could not have imagined. Each court decision effectively “updates” the Constitution, keeping it relevant for modern life.

- 02. Amendments as reflections of the times

Beyond judicial interpretation, the Constitution evolves through amendments, reflecting social and cultural changes. Examples:

- 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments

Responses to the Civil War: abolition of slavery and guaranteeing equal protection under the law. - 19th Amendment

Recognized women’s right to vote, reflecting the struggle for gender equality and political participation. - 26th Amendment

Lowered voting age to 18 during the 1960s protest movements, acknowledging youth engagement in civil rights and anti-war activism. The Constitution, therefore, did not “freeze” in the 18th century — it grows with society, adopting new forms and rules of the game.

- 03. The Constitution tested by time

The American Constitution has survived numerous crises that might have broken any other document:

- The Civil War and issues of state sovereignty;

- The Great Depression of the 1930s, which required new social and economic approaches;

- The protest movements of the 1960s demanding civil rights reforms;

- Modern challenges, from digital privacy to immigration policy and environmental threats.

Each time, the Constitution has served as a foundation for solutions, remaining a “compass” rather than a relic under glass.

Even for travelers, the Constitution manifests in everyday life:

- Museums and national archives display original texts and amendments.

- Tours of Washington, D.C. often include stories of how the Constitution affects citizens today.

- Experiencing the “living Constitution” helps people understand American culture and values, showing that freedom and rights are not abstract — they actively shape society.

The U.S. Constitution is not just history — it is a living experience, one that can be felt and observed in real life.

Separation of Powers and Checks and Balances: How the Constitution Governs the Country

One of the most brilliant and enduring solutions of the Founding Fathers was the separation of powers. They understood that any concentration of power could threaten the freedom of citizens. The U.S. Constitution created a system in which the legislative, executive, and judicial branches operate independently, yet remain interconnected, constantly checking and balancing each other. This model not only prevents abuses of power but also allows the country to respond flexibly to new challenges.

- 01. Legislative Branch: Congress as the “heart of democracy”

Congress consists of two chambers: the Senate and the House of Representatives.

- The House of Representatives reflects the population size of the states — the larger the state, the more representatives it has.

- The Senate guarantees equality among the states — two senators from each state, regardless of size.

Congress’s responsibilities include passing federal laws, approving the budget and taxes, declaring war, confirming appointments to the Supreme Court and other high offices, and overseeing the executive branch.

Each year, Congress considers thousands of bills, but due to the system of checks and balances, only a few dozen are actually enacted. This makes the process slow but carefully balanced.

- 02. Executive Branch: the President as the “face of the state”

The President is the head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. They sign or veto laws passed by Congress, appoint judges, ambassadors, and ministers (with Senate approval), conduct foreign policy, and can exercise emergency powers in crisis situations.

Even the President does not have absolute authority: a veto can be overridden by a two-thirds majority in Congress, and appointments require Senate consent. - 03. Judicial Branch: the Supreme Court as the arbiter

The Supreme Court determines whether laws comply with the Constitution.

- Judges are appointed for life to ensure independence.

- The Court can strike down laws and executive actions that contradict the Constitution.

Examples: - The Marbury v. Madison (1803) decision established the principle of judicial review — for the first time, the judicial branch gained the authority to assess the constitutionality of laws.

- The Court continually interprets the rights and responsibilities of citizens, taking into account modern conditions (for example, digital privacy and freedom of speech on the internet).

- 04. Checks and Balances

The Constitution established a mechanism where each branch of government monitors the others:

- Legislative

Can override the President’s veto, confirm judicial appointments, and carry out impeachments. - Executive

Can veto laws, appoint judges and officials. - Judicial

Can declare laws and executive actions unconstitutional.

This system prevented the U.S. from turning into a dictatorship during critical moments in history, including the Civil War and the Great Depression.

The system of checks and balances makes the American Constitution living and effective, allowing the country to maintain a balance of power and protect citizens’ freedoms for over two centuries.

Rights and Freedoms of Citizens in Modern USA: The Constitution in Action

The U.S. Constitution does more than outline the structure of government — it protects the rights and freedoms of every individual. These guarantees are visible in everyday life and make the United States a country where laws genuinely serve the people. For tourists, this is especially fascinating: even a stroll through cities or a visit to museums can reveal how the Constitution shapes society.

- 01. Freedom of Speech, the Press, and Assembly

The First Amendment guarantees the right to express opinions, participate in rallies, publish articles, and practice religion without government interference. Examples today:

- Journalists freely investigate government activities, including federal and local authorities.

- City squares and parks are open for rallies and protests that comply with the law.

- Tourists often witness live demonstrations and cultural events where people exercise their right to assemble.

Across the U.S., thousands of small towns hold annual “Freedom of Speech Days”, where students learn public debate — a direct legacy of the First Amendment.

- 02. Right to Privacy and Protection from Unreasonable Searches

The Fourth Amendment protects personal privacy: police cannot search homes or seize property without a warrant. Today, this applies even in the digital realm:

- Courts regularly hear cases concerning the protection of emails and smartphone data.

- Tourists can use the internet freely, without fear of government monitoring every message.

- 03. Rights of the Accused and Legal Protections

The Fifth and Sixth Amendments guarantee the right to remain silent, a fair and speedy trial, counsel, and jury trials, as well as protection from double jeopardy. Examples:

- In U.S. courts, tourists can observe trials where all these rights are respected.

- Popular TV shows and movies about courts are based on these constitutional principles.

- 04. Equal Protection under the Law

The Fourteenth Amendment ensures that all citizens have equal rights regardless of race, gender, or background.

- In schools and universities, principles of non-discrimination are strictly observed.

- Workplaces and public spaces are legally protected from arbitrary treatment.

- Tourists notice equal access to museums, parks, and public buildings.

- 05. Freedom of Religion and Cultural Diversity

The Constitution guarantees freedom of religion.

- Dozens of religions coexist in the U.S., with temples and churches open to everyone.

- Museums and cultural centers often showcase the religious traditions of different communities, allowing tourists to see how the law protects this freedom in practice.

Interesting fact: At the National Archives in Washington, tourists can view the original texts of the Constitution and the first ten amendments. Interactive tours even allow visitors to “play the role of a judge” and understand how rights and freedoms operate.

The living Constitution, with its amendments and system of checks and balances, makes the United States a unique country where laws truly protect individuals. It is not a museum relic — it breathes, evolves, and affects the life of every person, including tourists who come to experience America in all its freedom and diversity.

The Constitution as the Heart of American Culture: From the Classroom to Hollywood

For Americans, the Constitution is more than just a legal document. It permeates the entire fabric of society, becoming a symbol of freedom, democracy, and national identity. Its influence is felt everywhere: in education, politics, art, and popular culture. Understanding how the Constitution lives in the country’s cultural life helps tourists grasp the spirit of the U.S. on a deeper level.

- 01. The Constitution in Education: First Lessons in Freedom

American children encounter the Constitution almost from the first years of school:

- In elementary school, they study the Preamble and basic citizens’ rights.

- In higher grades, students discuss the amendments, the separation of powers, and the system of checks and balances.

- School projects and debates on constitutional topics develop critical thinking and understanding of democracy.

Some schools hold “mock trials” and “constitutional debates,” where students act as judges, lawyers, and jurors. This makes the Constitution a living educational tool rather than a dry text.

- 02. The Constitution in Politics: The Language of Power

Politicians at all levels constantly reference the Constitution:

- Presidential debates and congressional speeches quote amendments to justify decisions and laws.

- The Supreme Court often becomes the arena for national debates, where the Constitution serves as the final argument.

- Political campaigns use constitutional symbolism to emphasize commitment to freedoms and citizens’ rights.

These references show that the Constitution is not a museum relic but an active tool of political dialogue.

- 03. The Constitution in Popular Culture

The Constitution also permeates entertainment, bringing themes of freedom and rights closer to everyone:

- Films and TV series

Characters quote amendments, conduct court cases, and defend rights, demonstrating how the Constitution works in practice. Examples include Judge Dredd and popular legal dramas. - Music

Songs about freedom, equality, and civil rights reflect the spirit of the Constitution. This is especially evident in rock, hip-hop, and folk genres. - Theater and Literature

Plays and novels explore the struggle for rights, civic responsibility, and the Constitution’s influence on society.

During Constitution Day on September 17, theatrical performances take place nationwide, where actors in 18th-century costumes read the text of the document, making it accessible for all ages.

Thus, the U.S. Constitution is a living cultural code that shapes public consciousness, influences creativity, politics, and education. It makes Americans citizens aware of their rights and freedoms, and it helps tourists understand that freedom in the U.S. is not an abstract idea but a tangible part of daily life.

The U.S. Constitution as a Global Legacy: Lessons in Democracy for the World

The American Constitution is not only a symbol of freedom for the United States but also a global benchmark for building democratic states. Its influence is felt far beyond U.S. borders: from legislative halls in Europe to educational programs in Asia and Africa. Understanding how the Constitution shapes global politics and law reveals its significance as a universal tool for protecting rights and freedoms.

- 01. A Model for Other Countries

When countries drafted their first modern constitutions, they often looked to the U.S. as an example:

- France and Latin American countries in the 18th–19th centuries adopted ideas of separation of powers and human rights;

- Japan and Germany after World War II borrowed the system of checks and balances to prevent the concentration of power;

- Many African and Asian nations included amendments guaranteeing freedom of speech, assembly, and religion, inspired by the American experience.

The U.S. Constitution demonstrated that even a relatively short document (around 4,600 words) can become a powerful instrument of national and international stability.

- 02. Human Rights at the Core of the Law

The U.S. Constitution was one of the first documents to enshrine human rights at the level of fundamental law, rather than merely in a declaration.

- The 1st Amendment guaranteed freedom of speech, religion, and assembly;

- The 4th and 5th Amendments protected privacy and the rights of the accused;

- The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments abolished slavery and ensured equal protection under the law.

These principles inspired international documents such as the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948).

- 03. Checks and Balances as a Global Standard

The separation-of-powers model developed by the American Founding Fathers became universal:

- Legislative, executive, and judicial branches now exist in nearly all democratic countries;

- The system of checks prevents concentration of power and ensures balance between institutions;

- Judicial oversight of government actions is a direct legacy of American practice.

Many new democracies in the 19th–20th centuries invited American lawyers and advisors to help draft constitutions and judicial institutions because the U.S. model was considered time-tested and reliable.

- 04. The U.S. Constitution and Global Culture

The Constitution also shapes cultural perceptions of freedom:

- In world literature and cinema, American amendments are often cited as symbols of justice;

- International human rights conferences use it as an example of an effective balance between citizens’ rights and state responsibilities;

- Education abroad includes the study of the U.S. Constitution as a key case in democratic governance.

The American Constitution is a living history, a universal lesson in democracy, and a symbol of freedom that continues to inspire countries and citizens around the world.

Why You Should Experience “Living History” with American Butler

The U.S. Constitution is not a dull text tucked away in an archive. It is a living document that influences millions of court cases. It has endured centuries, revolutions, crises, and wars, remaining a symbol of freedom and justice.

And if you want more than just reading about it in textbooks — if you want to truly feel the atmosphere of American democracy — it’s time to take a step forward.

We organize for you:

- Tours to Washington, including visits to the National Archives, where the original Constitution is kept;

- Cultural and educational trips dedicated to U.S. history;

- Custom itineraries through cities where American history was made — Philadelphia, Boston, and New York.

With American Butler, you can experience genuine “living history”, see where democracy was born, and understand why the U.S. Constitution continues to inspire the world.